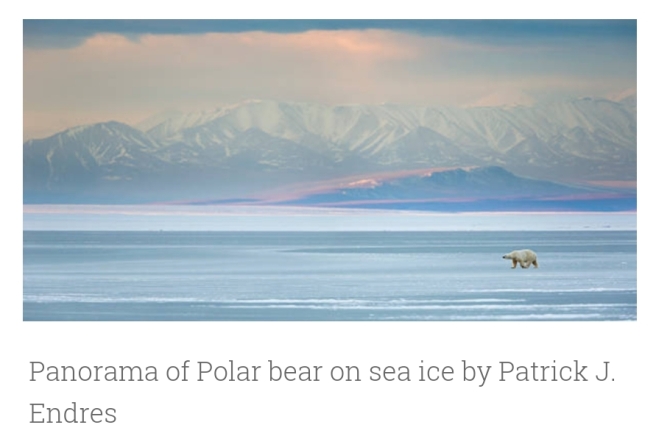

Drilling in the heart of “America’s Serengeti” is unconscionable, would cause irreparable harm, and leave this precious and fragile ecosystem forever altered.

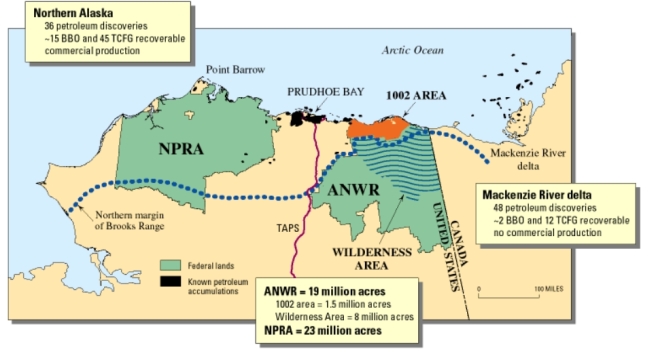

Deemed “the sacred place where life begins” by Alaska’s native Gwich’in people, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) possesses massive environmental and cultural importance. Spanning approximately 19.2 million acres across northeastern Alaska, the ANWR is part of the National Wildlife Refuge System, one of 16 refuges in Alaska.

The ANWR is also home to an impressive collection of wildlife; with 42 fish species, 37 land mammals, 8 marine mammals, and over 200 resident and migratory bird species, the Refuge is one of the most diverse areas in the arctic, with several notable species including polar bears, musk oxen, and caribou.

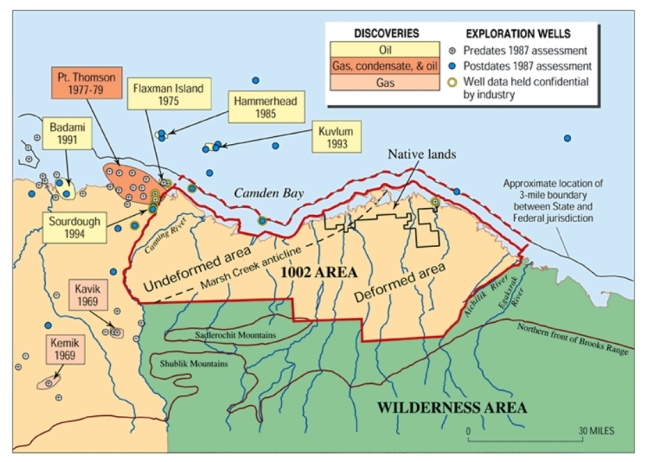

The Refuge was established in 1960 to preserve and protect its unique wilderness, abundant wildlife, and recreational value as post WWII construction and resource development raised concerns about environmental losses. Years of debate within Congress eventually led to the passage of the 1980 Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), doubling the size of the Refuge and deeming most of the original range as “wilderness.” All areas not allocated as “wilderness” became the “1002 Area,” named after Section 1002 of ANILCA which describes the specific data Congress would need before it could designate the area as “wilderness” or permit oil development.

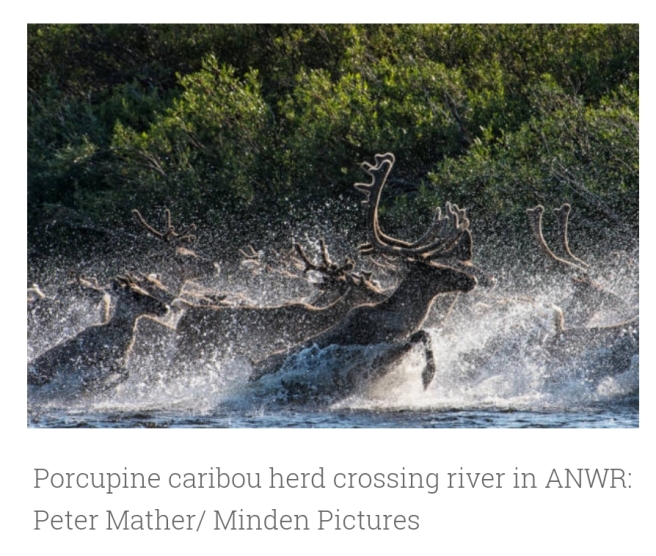

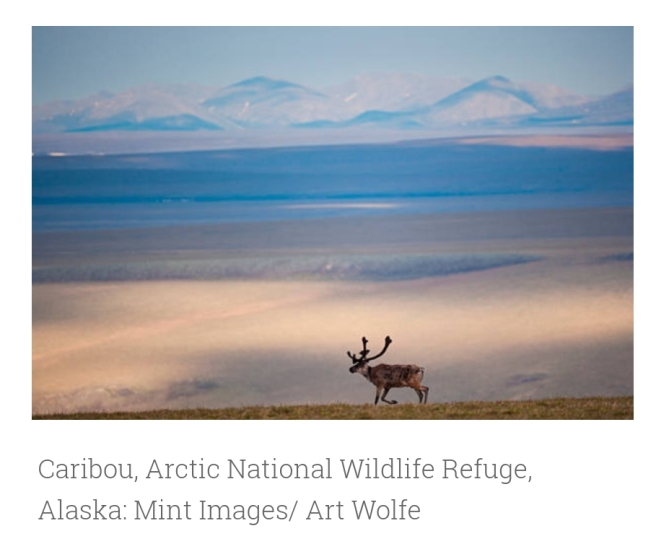

Many wildlife species rely on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) for their habitat including polar bears, musk oxen and wolverines. However, the species that relies heaviest on the ANWR is the caribou, specifically the Porcupine caribou herd. According to the last census in July 2017, the population of the porcupine caribou herd is currently approximately 218,000 individuals. This makes it the fifth largest herd of migratory caribou in North America. The majority of the year, caribou’s habitat ranges from Northeastern Alaska into Northwestern Canada, with an exception of summer where they migrate to annual calving grounds. Most of these crucial calving grounds are located on the coastal plain of the ANWR (Area 1002) that holds “potentially large oil and gas resources.” When, and if, the 1002 area is available for oil exploration and drilling, it will play a major role on the caribous’ lifestyle.

The Porcupine caribou herd are drawn to the coastal plains of the 1002 area for calving every year in late May or early June. By this time of the year the plains are usually free of snow, with plenty of vegetation, which increases camouflage and decreases predation. They give birth to the calves here (usually one per adult female) and stay in the nutrient rich habitat for about 3 weeks. Because so many caribou come to area 1002, it has been regarded as a concentrated calving zone, an essential area which nurtures the largest number of parturient females (caribou that are about to give birth or caribou that have just given birth, and their calves).

Another species that will be affected by oil drilling in the ANWR is the muskox. Native to Alaska, the muskox were extirpated by the 1920’s. In 1930, 34 muskox captured in East Greenland were transplanted to Alaska, and all muskox today are descended from these animals. The muskox were locally driven to extinction in the 1002 area in the late 1800’s and were later reestablished in 1969.

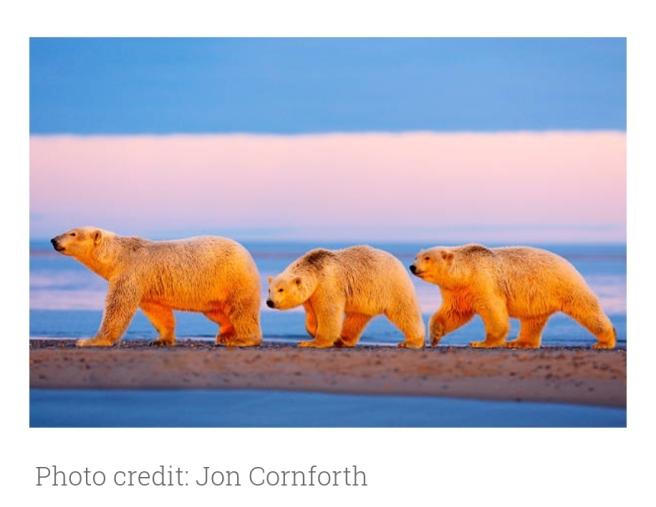

Polar bears are also a major concern when considering of the harmful effects oil drilling. A declining population of polar bears reside in the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge, and are one of only two subpopulations of polar bears in the United States. Known as the Southern Beaufort Sea population, approximately 900 individuals remain (at last count), and are listed as threatened wherever found.

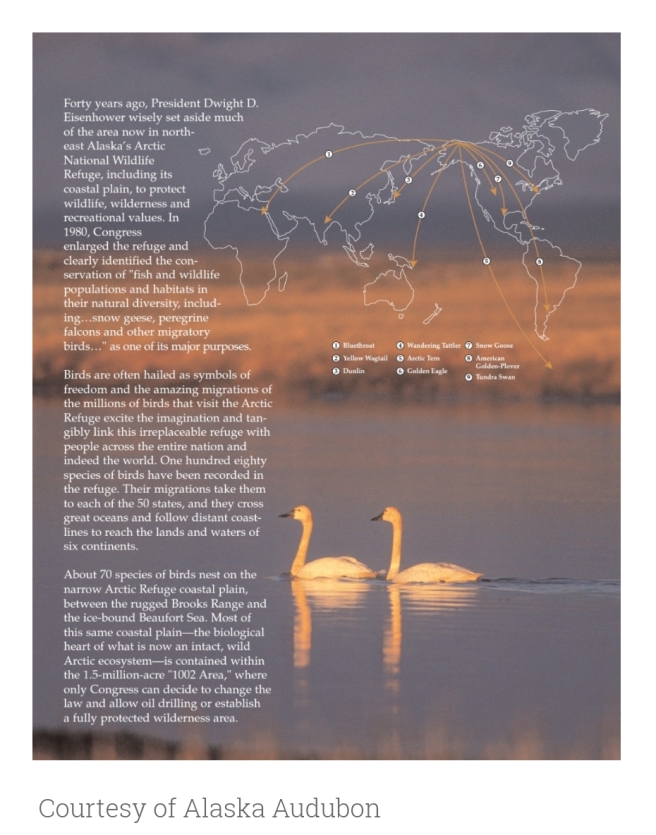

The world’s birds would also be threatened by drilling in the arctic refuge. No matter where you live in the United States, it’s very likely that some of your favorite local birds were born in the Arctic Refuge and return each year to raise their young. It is one of the most important bird nurseries on the planet and supports millions of birds that migrate from Alaska to every other state and six continents.

Environmental Impacts of drilling in the ANWR (general). In-depth information on impacts to wildlife below.

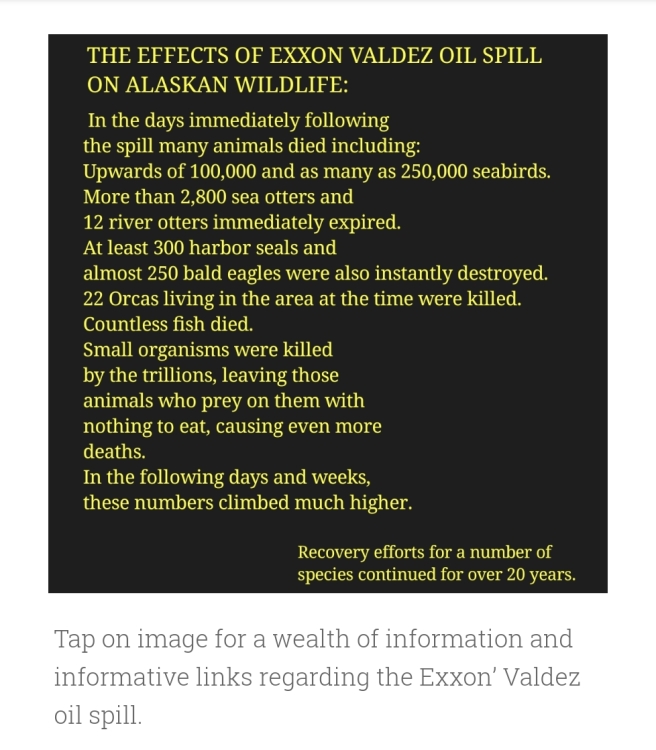

• Experts say an oil spill would be inevitable. Offshore drilling threatens our oceans, marine wildlife, and terrestrial wildlife with the risk of catastrophic oil spills. The Interior Department estimates a 75% chance of a major oil spill in the Arctic’s Chukchi Sea from just a single lease sale. Oil spills can also take numerous years to clean up. Nearly 20 years after the Exxon Valdez spill, more than 26,000 gallons of oil still remain in shoreline soils. Sadly, oil spills take place on a relatively consistent basis. Each year, about 880,000 gallons of oil are sent to the ocean from U.S. drilling operations.

• The challenges for cleaning up an oil spill in the Arctic are numerous. There are no viable methods of cleaning up oil from ice, and, in addition to adverse weather conditions, much of the area where drilling would take place is remote. Responding to an oil spill is extremely challenging in any marine environment, much more so in the Arctic. The period when it would be possible to clean up an oil spill is restricted to four to five months by darkness, heavy ice, and extreme cold. These severe conditions would make it impossible to attempt an oil spill cleanup for half the time during the operating season, and 100 percent of the time during the winter.

• Difficulties with an under-ice oil spill. If crude oil is spilled in the ocean, it normally floats. But if the oil is released or spilled under a lid of sea ice, it will be trapped under the ice.

In order to evaluate the enviromental consequences of an under-ice oil spill, you need to know when and if the oil will come to the surface, how far the ice will drift before the oil surfaces, and how much of the oil will be trapped in the ice when the ice finally melts.

Sea ice is more like a sponge than a solid substance. The channels and pores in the sea ice are different depending upon where they are located in the ice. At it’s surface, where ice is in contact with cold air temperatures, sea ice has smaller and less connected pores. Oil will normally only enter larger pores and also needs to push the seawater out of the pores. During wintertime, the ice is often too cold at the surface to allow for this, and the oil will be trapped. But during spring, or when the ice warms in warm weather, oil may migrate to the surface. Once the oil surfaces, time is of the essence. The only realistic approach to remove this oil from the surface of a closed ice cover is to burn it. However, most of the oil can only be burned during a window of opportunity of typically one week. After a week, the oil is said to be weathered, ie., it has lost certain components and mixed with water and can no longer be removed by burning it. This oil then threatens the arctic ecosystem (Sønke Maus/NTNU).

• Despite monitoring systems in place to prevent spills, a leak occurred in a pipe leading to the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) that went undetected for several days, spilling 267,000 gallons of crude oil (Barringer, 2006). Other spills directly related to land transportation of Alaskan oil include 700,000 gallons spilled when vandals destroyed a section of TAPS in 1978, and 285,000 gallons when a hunter shot the pipeline in 2001. Just as environmental assessments of TAPS have recognized and anticipated that oil spills happen and have consequences for environmental quality (Bureau of Land Management, 2002), the same consideration is necessary when evaluating the environmental impacts of drilling in ANWR.

• The Arctic is one of our last and greatest unspoiled wild places. No oil company has ever successfully drilled for oil in the pristine, wildlife-filled public waters of the Arctic Ocean despite an expensive and near catastrophic attempt by Shell Oil to explore for oil there in 2012, when a Shell drilling rig ran aground in a storm. Drilling here would threaten one of our planet’s most fragile, and remote ecosystems.

• Exploration—Seismic Surveys: Seismic surveys, also referred to as ‘air gun blasting’, are conducted to locate and estimate the size of an offshore oil reserve. In order to conduct surveys, ships use ‘airgun arrays’ to emit high-decibel explosive impulses to map the seafloor. The noise from seismic surveys can damage or kill marine life. High decibels are known to reduce the presence of zooplankton, impair fish eggs and larvae, and temporarily if not permanently deafen adults and juveniles. Without the ability to hear, fish and marine mammals struggle to communicate, navigate, avoid predators, and locate prey. These disturbances can also disrupt important migratory patterns, forcing marine life away from suitable habitats meant for foraging and mating. In addition, seismic surveys have been implicated in whale beaching and stranding incidents.

• Drilling and Processing Oil: The process of drilling releases thousands of gallons of polluted water, known as “drilling muds”. These muds contain toxins like benzene, zinc, arsenic, radioactive materials, and other contaminants used to lubricate drill bits and maintain pressure. Unfortunately, discharges are unregulated. High concentrations of metals were found around drilling platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. A study by PEW Charitable Trust concluded that a single oil well discharges around 1,500 – 2,000 tons of waste material. Contaminants from oil drilling accumulate on the sea floor; smother organisms and cause malformations, genetic damage, and mortality in fish embryos.

The Porcupine caribou herd

Since the nutrient-rich coastal plain is so critical for calving, disturbances caused by oil drilling would most likely both decrease the population of the Porcupine caribou herd and displace the herd to other, less suitable, calving sites outside of the 1002 area:

Research has found that female caribou with calves move

a minimum of 1.5–2 miles away from drilling infrastructure, such as roads and pipelines. Scientists predict that such deterrence in ANWR would adversely affect calf survival and population levels. Specifically, development in ANWR is predicted to displace the Porcupine Herd by 30 miles and reduce calf survival by 8.2%. Such a reduction is likely to reduce the Herd population as a whole, as a 4.6% reduction in calf survival would be expected to halt population growth (Griffith et al., 2002)*. The 8.2% reduction in calf survival would cause the growth rate of the population to decrease dramatically and the herd would decrease in numbers since a greater number of individuals are dying than being born. This would be devastating for the population of the Porcupine caribou herd. The coastal plain (Area 1002) is vital habitat for the caribou in order to maintain their population. In previous years when the Porcupine herd were unable to reach the 1002 area and forced to calf elsewhere (due to a large amount of snow on the coastal plains), June calf survival dropped by 19% (Griffith et al., 2002, p. 34). This rarely occurs, but if oil drilling was to eventuate in this area there would be similar results every year directly due to displacement.

In nearby Prudhoe Bay, where oil drilling does take place, the caribou that calve there, called the Central Arctic herd, were shown to move their calving area 4 miles away from drilling infrastructure, confirming that it caused a disturbance to the caribou (Griffith et al., 2002, p. 31). A displacement would have severe consequences for the Porcupine herd, and their ability to thrive, as their population is much larger than the Central Arctic herd, and, as less nutrient rich land is available in the surrounding area of the calving zone. This lack of high quality habitat, coupled with increased predation diminishes calf survival (Griffith et al., 2002, p. 34).

The Herd would likely be displaced to the south for calving ground which is composed of more foothills and mountains. The two major predators of caribou (grizzly bears and wolves) are usually more abundant, in both the foothills and mountains, where the caribou would be displaced to. A study done by Griffith et al. (2002), measured the abundances of these two predators in three habitat types, coastal plains, foothills, and mountains (p. 51). Grizzly bears were found to primarily stay in the foothills with a few wandering to the coastal plain to feed on the caribou (Griffith et al., 2002, p. 51). It was also noted that all of the active wolf dens in the area were in the mountains except for one which was found in the foothills. According to Griffith et al. (2002), there has not been a reported case of a wolf den on the coastal plains of the ANWR (p. 51). If the caribou were forced south, towards the foothills and mountains, they would be at a much higher risk of predation since both grizzly bears and wolves are at a greater density in these area.

Another issue the caribou face is insect harassment, in particular, from mosquitoes. After calving occurs, the Herd will move towards the coast to try to seek relief from these insects (Corn, 2003, p. 59). Oil development in the 1002 area could reduce the access to these important habitats. According to Clough, Patton, and Christiansen (1987), if caribou cannot freely move to a lower density insect habitat there could be severe consequences of disease, or death, brought on by the insects (p. 122). The proposed main pipeline for the 1002 area would bisect the calving grounds causing disturbance in the center of the crucial habitat (Clough, Patton, & Christiansen, 1987, p. 98), creating a tremendous barrier for the herd; other large herds of insect-harassed caribou have been observed to not travel under pipelines and have been seen to run up to 20 miles out of their way in order to go around the pipeline rather than passing under (Clough, Patton, & Christiansen, 1987, p. 112). The end result would be a reduced use of land north of the pipeline which contains approximately 52 percent of the total insect relief habitat (Clough, Patton, & Christiansen, 1987, p. 112). To escape the insects the caribou would likely travel south towards the foothills where, as mentioned earlier, there is a much greater risk of predation.

(*Griffith et al. (2002) “Section 3: The Porcupine Caribou Herd.” Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries. US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey. Biological Science Report USGS/BRD/BSR-2002-0001.)

Muskox

Another species that will be affected by oil drilling in the ANWR is the muskox. They were locally driven to extinction in the 1002 area in the late 1800’s and were later reestablished in 1969. There are currently less than 250 individuals that reside on the coastal plain, and their numbers have been declining since the late 1990’s (Griffith et al., 2002, p.62 and USGS, 2018, p.7). Muskoxen are year round inhabitants of the 1002 area and therefore would be in the area during the winter when most of the oil exploration and construction would take place.

Muskoxen conserve energy during the winter by nearly shutting down their metabolism and moving as little as possible (Corn, 2003, p. 63). Any type of disturbance during this time would adversely affect the muskoxen and could force the animals to expend all their energy reserves needed for winter survival (Corn, 2003, p. 63). Clough, Patton, and Christiansen (1987) write that muskox could lose about 2,700 acres of habitat directly from oil drilling; more when factoring in any type of human disturbance, which would likely discourage the muskoxen from using their preferred habitats (p. 124).

Muskox rely heavily on riparian zones for foraging and better snow conditions, any type of displacement from these areas would negatively impact energy needs and predation would dramatically increase. According to Clough, Patton, and Christiansen (1987), muskox respond heavily to seismic vehicles and have been reported to flee for about 0.6 miles after a disturbance from a seismic vehicle that was about 1.9 miles away (p. 124). They have also been found to stay nearly 2 miles away from seismic lines (Clough, Patton, & Christiansen, 1987, p. 124).

Polar Bears

Polar bears are a major concern when considering of the harmful effects oil drilling. A declining population of polar bears reside in the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge, and are one of only two subpopulations of polar bears in the United States. Known as the Southern Beaufort Sea population, approximately 900 individuals (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2017, para. 2) remain (at last count), and are listed as threatened wherever found.

This already declining population is facing a very real threat in the face of climate change and arctic oil drilling Polar bears experienced a 40 percent population loss between 2001-2010 from 1,500 to 900 bears during a period of sea ice decline (Jeffery F. Bromaghin, et al., Polar bear population dynamics, Ecological Applications). (50 percent population decline through 2018.)

One fundamental issue in planning for ANWR oil development is choosing the most appropriate time of year to enter the Refuge for drilling. In an attempt to minimize their environmental impacts, several oil companies proposed limiting their activity in the Refuge to winter thus reducing the harm to the majority of species in the area. This plan, of course, would be severely detrimental to polar bears, as winter is when polar bear denning occurs (Corn, 2003, p. 62), making them particularly sensitive to disturbances. Every October/November, female bears move onshore, to coastal areas, where they then dig a den in November, and give birth to one to three cubs in December or January. The mother and her new cubs do not emerge from their den until March or April (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2017, para. 3). The ANWR possesses the highest density of onshore dens of any area (approximately 43%) along the Alaskan coastline (Corn, 2003, p. 61), making it, by far, America’s most important onshore denning habitat for polar bears. One reason for this may be that the Refuge coastal plain and northern foothills have more uneven terrain than areas to the west, allowing snow drifts to form more readily (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2017).

With a large number of denning individuals in the area, threats from drilling could have significant impacts on the Refuge’s bear population.

Several studies found that female polar bears are highly sensitive to even slight human disturbance and will often respond by abandoning their cubs (Corn, 2003, p. 61). Aside from the drilling itself, other oil-related processes, such as seismic blasts, drive mother bears away from their cubs. In 1985, a pregnant polar bear in the Refuge was observed abandoning her soon-to-be birthing den after she was disturbed by seismic activity from what was considered to be the most intensive monitoring program ever in place for seismic exploration (Garner, G.W. and P.E. Reynolds. 1986. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain resource assessment: final report, baseline study of the fish, wildlife, and their habitats. Section 1002c, ANILCA. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Anchorage, p. 158.) – evidence that these bears would be highly responsive to even the most state-of-the-art ANWR drilling program.

As polar bear denning occurs both on mainland areas and on annual ice plains, polar bears’ denning behaviors will be heavily affected no matter where the drilling occurs, be it on the mainland or offshore, as any potential den displacement cannot simply be shifted outwards onto offshore ice islands, banks, and plains where drilling is not present. It is imperative to recognize the significant reduction in Arctic sea ice over the past few decades, thus reducing alternative denning areas. The decline of sea ice is a trend that is only expected to continue and potentially worsen. September Arctic sea ice is now declining at a rate of 13.2 percent per decade (NASA, Arctic Sea Ice Minimum, Scientific Visualization).

To further exacerbate this dreadful situation, a strikingly large proportion of the Southern Beaufort Sea polar bear population (nearly half) choose to make their dens on annual pack ice that has been declining since 1990 (Durner, Amstrup & Ambrosius, 2006, p. 35 also Bromaghin JF et al., Polar bear population dynamics in the southern Beaufort Sea during a period of sea ice decline link). However, as the sea ice melts, the polar bears are forced to seek out another area for denning purposes. It seems inevitable that the proportion of bears denning on the mainland in the Refuge will increase dramatically within the foreseeable future, a phenomenon that only further heightens the value of the Refuge for U.S. polar bears.

Polar bears in arctic regions use sea ice not only for denning habitat but for crucial hunting grounds of their main prey species: seals. Because of melting sea ice, it is likely that many polar bears will starve. A new study reveals that large carnivores need to eat 60 percent more than anyone had realized. The study also reveals polar bears’ utter dependence on seals (Anthony Pagano, USGS, Polar Bear Ecology and Conservation) – link.

The continuing decline of arctic sea ice, and reduced ability to capture a key food source, intensifies the many threats polar bears across the arctic, including the declining Beaufort Sea population, are facing. Arctic populations have declined in numbers by approximately 40 percent since the start of the millennium. In 2007, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that the total number of polar bears worldwide will shrink to just a third of its current size due to loss of habitat and decreased access to prey (link). In fact, some scientists believe that polar bears and other iconic animals could be extinct by the end of the century, emphasizing the need to protect critical habitat and marine areas, a primary tool for mitigating threats to marine biodiversity (link).

As polar bears are one of the most highly susceptible species to human-induced climate change, these magnificent creatures are already fighting a brutal uphill battle against prominent changes in fundamental habitat structure – a sad reality that is only forecasted to intensify. Further, the results from a study based in the 1002 Area of the Refuge suggest that climate change and oil development behave synergistically when their future potential impacts on wildlife habitat are analyzed in unison (Fuller, Morton, and Sarkar, 2008). In other words, the simultaneous occurrence of climate change and oil development would intensify both of their individual contributions to habitat reduction for polar bears, (in addition to ten other resident species). Fuller, Morton, and Sarkar (2008) conclude that shortfall from wildlife conservation targets in the 1002 Area is up to 35 times greater if the area is developed for oil drilling as opposed to being left intact, and affirm that their findings should provide Congress with critical insight for permanently proscribing oil development and designating it a protected wilderness area (p. 1556, link).

Birds

Approximately 200 species of birds have been recorded in the refuge. Their migrations take them to each of the 50 states; they cross oceans and follow distant coast-lines to reach the lands and waters of six continents. About 70 species of birds nest on the narrow Arctic Refuge coastal plain.

Out of the nearly 200 species of birds recorded in the refuge, 135 are known to use the 1002 area, including numerous shorebirds, waterfowl, loons, songbirds, and raptors.

Oil development in the Arctic Refuge would result in habitat loss, disturbance, and displacement or abandonment of important nesting, feeding, molting and staging areas.

One species of bird that could be greatly impacted by oil development is the snow goose. Large numbers of snow geese, varying each year from 15,000 to more than 300,000 birds, feed on the Arctic Refuge coastal tundra for three to four weeks each fall, on their way from nesting grounds on Banks Island in Canada to wintering grounds primarily in California’s Central Valley.

They feed on cottongrass and other plants to build up fat reserves in preparation for their journey south, eating as much as a third of their body weight every day. The rich vegetation of the coastal tundra enables them to increase fat reserves by 400% in only two to three weeks.

Because snow geese feed on small patches of vegetation that are widely distributed across the Refuge’s coastal tundra, a large area area is necessary to meet their needs. They are extremely sensitive to disturbance, often flying away from their feeding sites when human activities occur several miles distant. Oil exploration and development would displace snow geese from areas that are critically important for them. More than 80% of the feeding habitat preferred by Snow Geese within the

Arctic Refuge is located inside the 1002 Area, where they feed on the underground stem bases of cottongrass, a highly nutritious and digestible plant food (USFWS link). The U.S. Department of the Interior estimates that oil development could displace snow geese from as much as 45 percent of their preferred feeding habitat within the 1002 Area (USFWS. 2000). Potential impacts of proposed oil and gas development on the Arctic Refuge’s coastal plain). The combination of habitat loss, plus human disturbance, increased predation, and other indirect effects of oil development would reduce the value of the Arctic Refuge coastal plain for migratory birds. Over time, fewer birds would nest or stop in the refuge, and species with small, declining or vulnerable populations would be most at risk. In the event that an oil spill were to reach coastal lagoons, the threat to bird populations would increase dramatically. The loss of birdlife that would follow oil development in the Arctic Refuge’s coastal plain would be tragic. The loss of life following an oil spill, unconscionable.

For more information regarding the impacts of oil and gas development on birds, please see this page from Audubon Alaska.

The Exxon Valdez spill, though still one of the largest ever in the United States, has dropped from the top 50 internationally (view a list of top oil spills worldwide). It is widely considered the number one spill worldwide in terms of damage to the environment, however. The timing of the spill, the remote and spectacular location, the thousands of miles of rugged and wild shoreline, and the abundance of wildlife in the region combined to make it an environmental disaster well beyond the scope of other spills.

Polar bear at sunset: Sylvain Cordier

“If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it.”

“Once our natural splendor is destroyed, it can never be recaptured. And once man can no longer walk with beauty or wonder at nature, his spirit will wither and his sustenance be wasted.”

– Lyndon B. Johnson

– President of the United States

On this page you will find citations, related content and references. On this page you will find a tweetsheet.

Protect the Arctic Refuge

Consider purchasing a greeting card. The 20 cents profit from each card or postcard helps us provide advertisement-free content. Tap the image below for more information.

Feature Image by Patrick J. Endres

America’s Wildest Refuge: Discovering the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Copyright © 2018 [COPYRIGHT Intheshadowofthewolf]. All Rights Reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.