The following report shows the results of Intensive Management with “wolf control” in Upper Koyukuk Management Area within Game Management Unit 24B in Alaska. This predation control program was authorized by the Alaska Board of Game under 5 AAC 92.124 (c)

Note: The criteria for “success” with this program is a harvest of 35-40 moose in UKMA. The wolf removal objective is to reduce wolf numbers “as low as possible” in the UKMA near Allakaket and Alatna (combined human population of around 150) to allow more moose to be hunted by humans. The objective seeks to maintain a population of 100-140 wolves in all of GMU 24B “to ensure wolves persist in the area”. Keep in mind that GMU 24B is 13,523 square miles, the size of the predation control area is 1,360 square miles.

“Programs are conducted by selected resident citizen pilot/gunner teams that receive discretionary state permits authorizing same-day-airborne (SDA) landing and shooting and/or aerial shooting from aircraft. To obtain one of these permits, an application must be submitted to the department, and authorized pilots and gunners will be notified if selected. Nonresidents cannot participate in the wolf control program. Please note that this program is wolf control, not wolf hunting.”

Note that black and grizzly bears are likely the primary mortality factor effecting calf survival based on composition data and field studies in adjacent Game Management Units (21D and 24D) but they were not be included in predator control activities as local resident cultural taboos make bear control an untenable option.

Also note that nowhere in the report was there any mention of human induced mortality rates of moose neonates (a study many researchers would like to continue as it facilitates a more in-depth characterization and understanding of human-induced abandonment and some of its complexities). A study such as this was cancelled by Minnesota’s Governor, Mark Dayton, out of concern that human interference is harming the very animals it’s trying to help.

Intensive Management for Moose with Wolf Predation Control in GMU 24B (report prepared February 2015).

The culling of wolves in the UKMA:

In year 1, regulatory year (RY*) 2011, no wolves were killed as part of the department control, however 2 wolves were hunted. The population of wolves in the UKMA at this time was estimated at 23-58.

In year 2, RY 2012, it was decided that prior to this year’s wolf control the population was approximately 36-37. From this small population 23 wolves were gunned down, leaving an “abundance” of 13-14 individuals.

In year 3, RY 2013, no wolves were killed; the department estimated the population to be 21-25 wolves.

In year 4, RY 2014, the “pre-control abundance” was estimated at 28 to 29 wolves of which the department gunned down 26, leaving an “abundance” of just 2 or 3 animals.

In year 5, RY 2015, the pre-control guesstimate was at 10 to 15 wolves, of which the department gunned down 10, leaving, again, just 2 or 3 individuals.

In year 6, the pre-control population remained at 2 or 3 wolves, however, by the end of the regulatory year the population was 10 to 15 animals.

The results of this horror story.

59 wolves lost their lives thanks to the intensive predator management program in order to increase human harvest of moose.

The calculated yearly harvest (human) of moose prior to the slaughter of these magnificent animals was 16. The last calculation offered by the department was in year 4 (RY 2014) when just 14 moose were harvested. Even worse was year 3, the first year after the wolf control began, when only 10 moose were harvested. No data was offered for 2015 or 2016.

The total cost (monetary) of this program was $660,900.00

With the signing into law of H.J.Resolution 69 our National Wildlife Refuges are now subject to this sort of mismanagement in Alaska, as the law strikes down the Alaska National Wildlife Refuges Rule. Should the State win a lawsuit against the National Park Service these practices will also resume in National Parks located in Alaska.

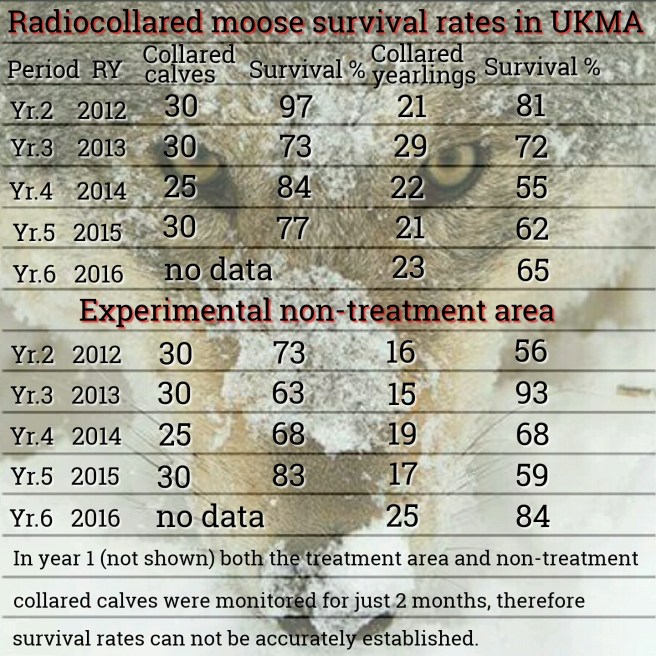

Composition of calves, yearling males and males are per 100 females:

An example of an active predator management program in the UYTPCA:

The control program in GMU units 12, 20(B), 20(D), 20(E), 20(A), and 25(C): the Upper Yukon-Tanana Predation Control Area (UYTPCA) was established to increase the Fortymile Caribou Herd throughout its range to aid in achieving intensive management objectives. This is a continuing control program that was first authorized by the Board of Game in 2004 for wolf and brown bear control, though in 2009 bear control was deleted from the program because control methods available at the time were deemed ineffective. The wolf population control objective for the area is 88-103 wolves. 1,423 wolves have been killed in this region between RY 2004 and RY 2015. The use of radio collars is one of the techniques used to locate and kill wolves in the Upper Yukon-Tanana area (the radio-collared wolves are often called “Judas Wolves”; approximately 28 wolves are collared for this purpose).

For more than two decades the National Park Service monitored the wolf packs in the Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, however, because so many wolves were killed by Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game the study was abandoned. Each of the preserve’s nine wolf packs lost members; three packs were entirely eliminated while another five packs had been reduced to a single wolf each. The Park Service officially ended the study in 2014.

Clearly, Alaska’s lethal predator control tactics are based on poor science and inadequate predator-prey population surveys, are unethical and prioritize consumptive use of wildlife over non-consumptive use. Increasing ungulate populations beyond carrying capacity degrades habitat and disrupts ecosystems. Furthermore the department has failed to produce scientific evidence that these programs have indeed produced larger herds of ungulates with increased human harvest.

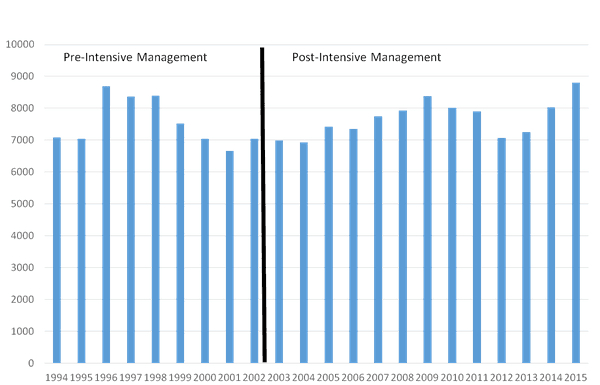

The graph below shows moose harvest for each year during the period starting when the intensive management law passed in 1994 and extending to 2015.

Compassion, kindness, sympathy and a humane treatment of wildlife are sorely needed as an integral part of Alaska’s wildlife management policies, with ethical standards that call for the protection of all wildlife, including wolves.

The Interim Annual Report on intensive management for Moose in the UKMA can be found here.

*Regulatory Year(RY) is July 1st to June 30th.

Copyright © 2017 [COPYRIGHT Intheshadowofthewolf, name and webpage]. All Rights Reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.